Raynaud’s 101: Why Your Fingers Change Color in the Cold

When the weather turns cold, it’s normal for our bodies to respond by tightening, or constricting, the tiny blood vessels in our fingers and toes. This is the body’s way of conserving heat and keeping our core warm. For many people, this narrowing of blood vessels is subtle and barely noticeable. But for others, this response becomes exaggerated, leading to dramatic color changes, discomfort, and sometimes more serious symptoms.

This phenomenon is called Raynaud’s (pronounced RAY-nodz).

Raynaud’s is extremely common, and for many people it’s mild and manageable. But in some cases, it can be a sign of an underlying autoimmune disease. Understanding the difference—and knowing when to seek help—is important for long-term health.

In this blog, we’ll cover everything you need to know about Raynaud’s, including symptoms, causes, risks, look-alike conditions, treatment options, and when to see a rheumatologist.

What Are the Typical Symptoms of Raynaud’s?

The hallmark sign of Raynaud’s is color changes in the fingers and toes when exposed to cold.

These color changes tend to occur in sequence:

White: Blood flow sharply decreases as the vessels constrict.

Blue: Lack of oxygen in the tissues causes a bluish hue.

Red: As blood flow returns, the fingers flush red, often accompanied by throbbing or warmth.

Patients often describe:

Numbness or tingling

Aching or burning pain

A pins-and-needles sensation during rewarming

Loss of dexterity during attacks

Sensitivity to even mild temperature changes

Symptoms are often triggered by cold weather, air conditioning, holding a cold drink, or stress.

Why Does Raynaud’s Happen?

The tiny blood vessels in our hands and feet are designed to adjust to temperature changes.

In cold environments, these vessels constrict to preserve body heat.

In Raynaud’s, this constriction is overactive or exaggerated, causing a temporary but significant reduction in blood flow. The reduced circulation leads to the dramatic color changes and discomfort that define Raynaud’s.

This exaggerated response can happen on its own (primary Raynaud’s) or as part of a broader autoimmune process (secondary Raynaud’s).

What Does It Mean if I Have Raynaud’s?

Raynaud’s itself refers to the pattern of cold-induced color changes, but the underlying cause varies.

Primary Raynaud’s

Occurs by itself

Not linked to autoimmune disease

Often mild

Does not cause tissue damag

Requires monitoring but is typically benign

Secondary Raynaud’s

Secondary Raynaud’s occurs as part of an underlying autoimmune or connective tissue disease. Conditions commonly associated with Raynaud’s include:

Scleroderma (almost all patients with scleroderma have Raynaud’s

Lupus

Myositis

Rheumatoid arthritis

Mixed connective tissue disease

Sjögren’s syndrome

Secondary Raynaud’s is generally more serious and may lead to ulcers, slow wound healing, or—in rare cases—gangrene if circulation is severely impaired.

Determining whether Raynaud’s is primary or secondary is the most important step in evaluation.

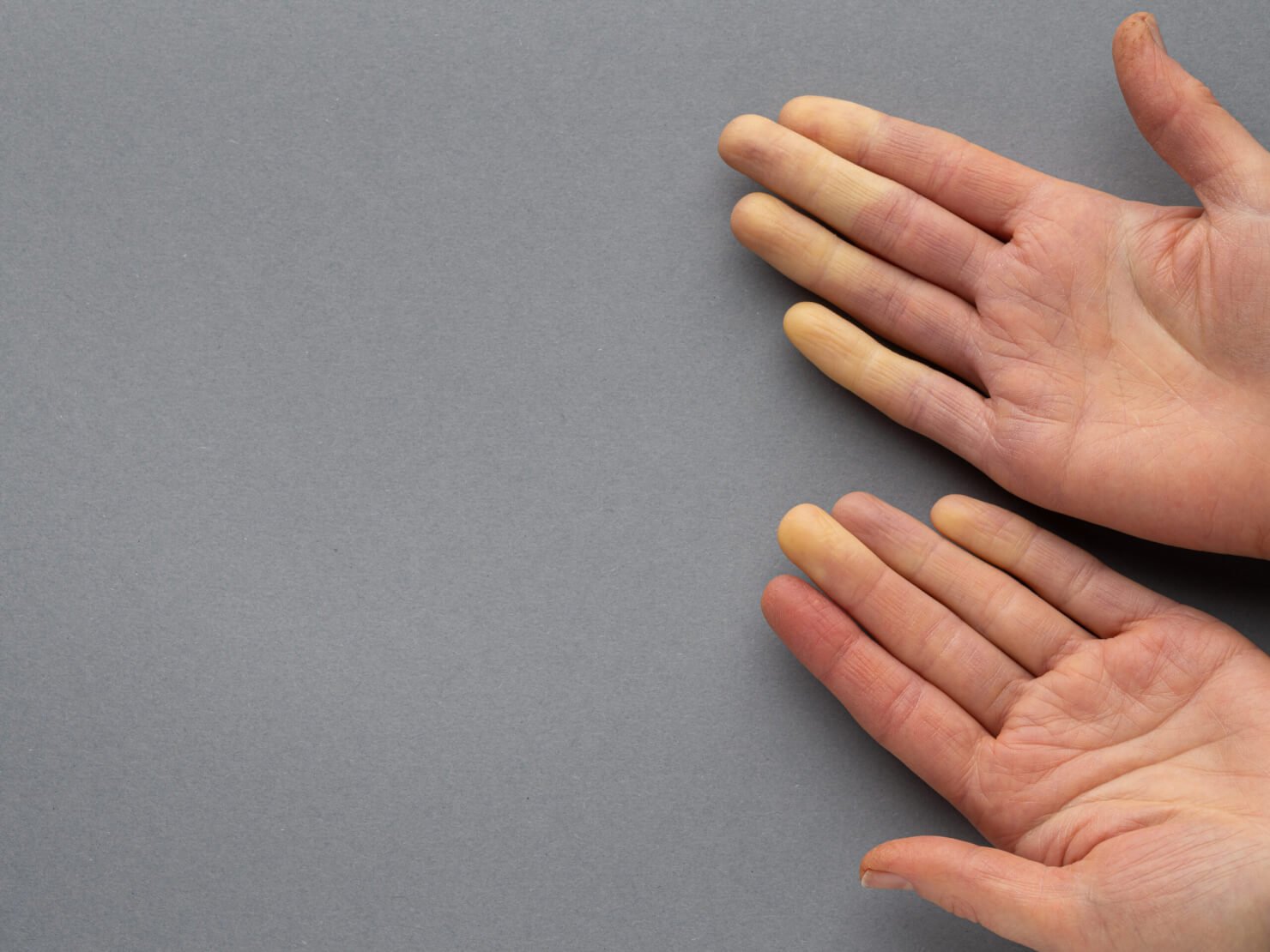

This is a picture from a colleague of mine, who has disruptive primary Raynaud’s symptoms. He is an Ironman athlete and during outdoor activities, his hands look like this.

This is an example of a patient of mine with blue discoloration in her toes due to Raynaud’s. Peripheral rewarming was not adequate, so we started her on a calcium channel blocker to improve circulation.

Why Should I See a Rheumatologist if I Suspect Raynaud’s?

Even if you feel otherwise completely healthy, it’s important to be evaluated early.

A rheumatologist will:

Take a thorough medical history

Perform a detailed physical exam

Evaluate your nailfold capillaries (tiny blood vessels near the nailbed)

Order rheumatologic laboratory tests

Determine whether the pattern is primary vs. secondary

Establish a baseline for future monitoring

Sometimes, patients with Raynaud’s feel perfectly fine but still have subtle laboratory abnormalities that require long-term follow-up. Early detection of autoimmune disease—ideally before major symptoms develop—can significantly improve outcomes.

The more proactive we are in identifying changes in health, the earlier we can intervene when necessary.

What If I Feel Fine Other Than Having Raynaud’s?

It’s still wise to be evaluated. Many autoimmune diseases start quietly, and Raynaud’s can be an early warning sign.

Even if your symptoms are mild, I recommend:

A full rheumatology evaluation

Baseline labs

Serial monitoring, when appropriate

This allows us to track for any evolution of disease over time and step in early if changes appear.

Additionally, not all color changes in the hands or feet are Raynaud’s—several other conditions can mimic it. This is another reason evaluation is important.

Conditions That Can Mimic Raynaud’s

Raynaud’s is common, but it’s not the only condition that causes color changes or pain in the fingers. Here are several other diagnoses to consider:

-

A dermatologic condition causing:

Redness

Burning pain

Symptoms triggered by heat or cold

This contrasts with Raynaud’s, where cold is the primary trigger.

-

A form of cutaneous lupus that leads to:

Painful red-purple lesions on the fingers or toes

Blistering or ulceration

Symptoms worsened by cold and damp environments

Often improves with topical steroids

Unlike Raynaud’s, these lesions can persist for days to weeks.

-

Compression of blood vessels or nerves under the clavicle causes:

Color changes

Numbness or tingling

Symptoms triggered by arm position, not temperature

Can affect pulse strength

-

A serious inflammatory disease of the blood vessels that may cause:

Pain

Purple discoloration

Ulcers

Systemic symptoms

Because vasculitis can reduce blood flow, it sometimes resembles Raynaud’s but tends to be more painful and persistent

-

A severe vascular disease seen primarily in smokers.

It causes:

Reduced circulation in the hands and feet

Pain and color changes

Risk of ulcers or gangrene

This is usually distinct from Raynaud’s but can appear similar at first glance.

Treatment depends on severity. Most patients start with simple, proactive measures:

1. Rewarming the Extremities

This is the foundation of treatment.

Helpful strategies include:

Always wearing gloves or mittens in cold weather

Layering socks and warm footwear

Using portable hand warmers (I love, love, love “HotHands”)

Think about bringing a portable heater to work if your office space is cold.

2. Topical Nitrates

For targeted improvement in circulation in one or two fingers.

3. Calcium Channel Blockers

If rewarming isn’t enough, we typically start with Amlodipine, Nifedipine, and other blood pressure medications. These medications help relax blood vessels and improve circulation.

4. Additional Therapies for Severe Cases

In secondary Raynaud’s or ulcer-forming disease, treatment may include:

PDE-5 inhibitors (like sildenafil)

Prostacyclin infusions

Treatment of the underlying autoimmune disease

Anti-platelet medication

How is Raynaud’s Treated?

Will My Raynaud’s Get Worse Over Time?

Not necessarily.

Primary Raynaud’s is often stable and may even improve with age.

Secondary Raynaud’s can worsen if the underlying autoimmune disease progresses, so monitoring is important.

Signs of More Severe Raynaud’s

Call your doctor promptly if you notice:

Persistent ulcers on the fingertips

Severe pain that does not improve with rewarming

Black discoloration indicating tissue death (gangrene)

What Is Gangrene?

Gangrene occurs when tissue loses blood flow for long periods. The area turns dark blue or black and becomes extremely painful.

This is a medical emergency.

Severe cases are rare and usually seen in secondary Raynaud’s associated with conditions like scleroderma or lupus.

In my own clinical practice, I have seen this occur in a subset of patients with Scleroderma, but it is not typical for the average person with Raynaud’s.

Raynaud’s causes cold-triggered color changes in the fingers and toes due to over-constriction of blood vessels.

Some people have primary Raynaud’s, which is benign. Others have secondary Raynaud’s, linked to autoimmune disease.

Early evaluation by a rheumatologist is important—even if you feel well—because Raynaud’s can sometimes be an early sign of autoimmune disease.

Several other conditions can mimic Raynaud’s, including erythromelalgia, chilblain lupus, vasculitis, Buerger’s disease, and thoracic outlet syndrome.

Treatment starts with diligent warming of the extremities; I especially recommend portable hand warmers like “HotHands”.

Raynaud’s doesn’t always worsen over time, but monitoring helps ensure early detection of any changes.